Kana K’iwacu (Children of Pain)

Patrick Shyaka

Background

On April 7, 1994, in Rwanda, members of the Interahamwe militia and presidential guard began the Genocide against the Tutsi. The mass slaughter lasted 100 days, taking the lives of more than a million souls, before being put to an end by the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF)-Inkotanyi in July 1994. This is dedicated to the survivors who strived to move on and Rwanda’s reconstruction journey.

MUSA LIVED ALONE by choice, but now he lived among people who’d lost their loved ones despite their choices. It was the beginning of the end. The year was 1994, and for the rest of the world, Kurt Cobain had just committed suicide, and Forrest Gump had become a massive box office success.

IN PARIS, INSIDE L’Arc nightclub, a shrill of extremely loud music and even louder exclamations of freedom among the youths reigned. They danced on top of the tables. They swallowed whatever was colourless. It was a party. The lights dizzied up any soul that attempted to follow them through the walls. No one could hear any other sound, not even their thoughts. While this happened, Musa, in his military uniform, made breakfast for his soldier friends sleeping in the bunker underneath the caves, nine thousand kilometres from France, in a little landlocked country middle of East Africa called Rwanda, where it was equally loud. The people were loud, not as exclamations of freedom, but pain. They screamed. They danced too, except on forest grounds. They drank whatever was colourless, but it was nothing like a party. No one could hear anyone’s thoughts; the silence of the dead was loud.

Musa heard his name called out from the walkie-talkie perched on his belt. The voice on the other side commanded him to take a squad and survey the next few kilometres on Nyanza Ridge before the rest of the rebel army taking back the country could march forward.

“Yes, Sir,” replied Musa, with the same bearing he had when they began the war against the government that had divided its people and launched a massacre, killing people with machetes, guns and bombs, in churches, in schools, in their own homes, and before their kids. It was the same bearing with which he held a gun for the first time despite being a refugee doctor. He took the other four soldiers with him through the sickening odour of decomposing bodies, skulls and bones, torn clothing, and scraps of paper scattered among the bushes.

“Fuck,” they repeatedly said in Kinyarwanda, and with no vomiting. They’d been used to this, to horrors. It was arguably the worst thing to be experienced in. Yet they were, and they continued to be, through Nyarubuye, where bodies lay twisted and heaped on benches and the floor of a church; in Nyamata, where the corpse of a little girl, otherwise intact, had been flattened by passing vehicles to the thinness of cardboard in front of the church steps; on the hills of Rebero, where pieces of human bodies had been thrown down the steep hillside; and in the Amahoro Stadium in Kigali, where the sun bleached fragments of bone in the grass of the playground and, in the stands, a small red sweater held together the ribcage of a decapitated child. They saw it all until they won, until they shot fires in the sky, demanded silence and peace, and chased the Interahamwe out of the country. No matter how long they showered, they couldn’t wash the images out of their minds. Eventually, Musa quit, returned his uniform and built a place up by Lake Muhazi.

Before he could deposit his war medals and walk away, his supervising officer had asked for one last task out of him.

“What is it?” inquired Musa, with his shaking hands and troubled eyesight.

“We need people to help clean the streets and the dead bodies,” the officer said. Musa nodded. What else was he to do? So, he cleaned. He thwarted the carcasses in the roads and the trees, and the bombed cars and destroyed churches were wiped clean. The smell stuck to his hands. They scrubbed everything and boxed the corpses with enough respect that they had once been more than mere corpses. A country-wide cleaning of dead bodies was ordered. In every district, sector and cell, people woke up, entered houses, and cleared the places of any corpses, guns or remains of either. They revisited death in its after-party and made sure to clean up after him. A new beginning had to be plonked fast, and that was it.

“NO BIRDS TODAY,” whispered Musa, gently holding one end of a disfigured body, namely the head. He and his friend slowly aligned it on top of the other three bodies in the trunk of a Pickup truck, slid the legs to fit in, and then closed it.

“There haven’t been any birds in the sky for months,” replied his friend. His name was Ruti.

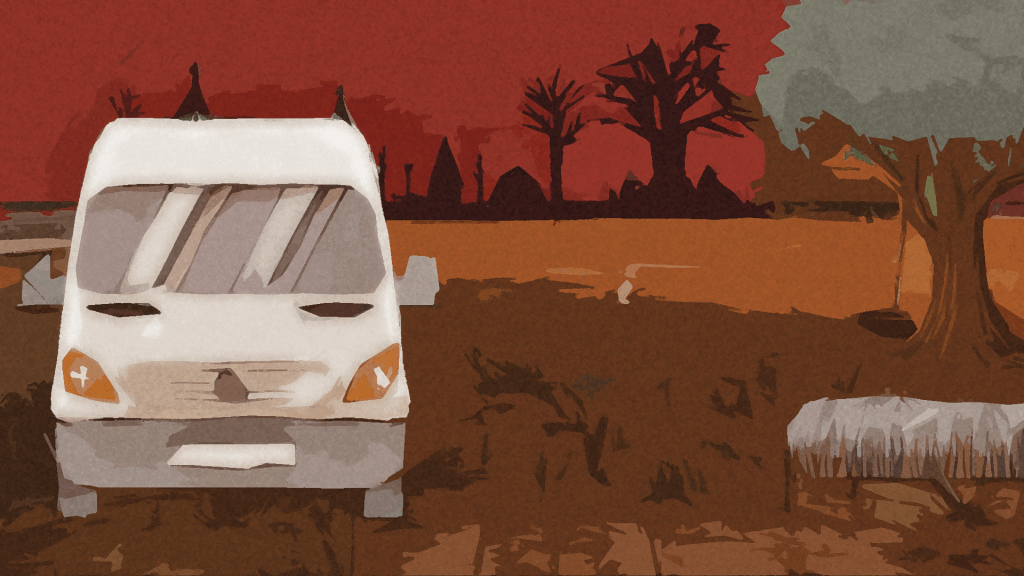

“I thought by now, something would have changed,” said Musa. They started the car. The streets were dusty and muddied in blood, and carcasses lay on every corner. A dozen men at every turn repainted the roads and loaded the last few corpses that remained to the morgues. Some of them were soldiers; some were survivors. In a matter of minutes, Musa and Ruti reached the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali (CHUK), where the pathologists examined the corpses, and close families attempted to identify their missing ones. They gently glided the bodies onto carts and inside the morgues, returned and did the tours over and over again until it was evening.

At home, Musa had a vintage Sharp TV he’d found in one of the houses they had cleaned weeks earlier. It could only broadcast channels from the Democratic Republic of Congo, but it was enough to distract and show him something different. The news channel mainly discussed ongoing battles east of Congo, Goma. They spoke of Rwandan soldiers who were partnering with Ugandans and other Congolese to fight the faction of killers harbouring there. Afterwards, he watched music videos he didn’t know how to feel about, involving many hip-thrusting moves. He heated some rice, beans and isombe. They tasted washed out, but he lived alone and spent his days smelling corpses covered in blackened blood. Taste was his last concern. Musa figured he would pass by the market and buy potatoes to cheer himself up, but he fell asleep. He couldn’t fully close his eyes because everything else surged like a nightmare.

In the morning, he passed a Gacaca—analogue court system—being held outside what became a sector office. He stopped his truck for a minute and watched as people queued on chairs testifying against the apprehended killers who stood mere metres from them beside a table, a judge, and their anger. The prosecutors were shouting to the convicts’ faces, and some of the victims present whimpered. Musa looked away. He understood the tragedies and knew first-hand how these people who’d lost their fathers and their daughters felt. Their cries were justifiable. Afterwards, he found Ruti waiting for him by the side of the road at the intersection of Shyorongi and Kigarama.

“You’re late,” exclaimed Ruti as he hopped in the passenger’s seat.

“The bodies aren’t going anywhere, are they?” said Musa. Ruti processed his words and nodded. It had not been a joke. They picked up a couple more handymen, descended the valley, and entered a deserted high school.

“We’re picking the dead bodies in the classrooms and putting them in the back until we have six or seven in the car,” announced Ruti to the handymen, “That’s when we’ll drive them to the market where they will get cleaned and come back for the rest, gutyo, gutyo.”

The men strung out of the pickup truck wearing gloves and marched slowly to the classes, spotting where the bodies lay. The windows were broken, the doors pulled down, holes dug in the middle of the schoolyard, and the smell of a slaughterhouse perched therein. Musa instructed one of the handymen to follow him through the holes, where he tried diligently not to damage the cadavers. They lifted the remains back to the ground, wrapped them into shrouds, and hoisted them into the truck.

“Be careful,” they reminded each other, subsequently irked by the view and the smell. Once in a while, one of the men would recognise the body of a friend and cry, and the rest would wait it out. When they headed to the Shyorongi market for the day’s last tour, Ruti asked Musa if he would accompany him to the Gacaca courts. “They are going to be prosecuting the Hutu that killed my two sisters,” he said.

Musa became silent. “I didn’t know you lost people in the genocide,” he finally said.

“Ain’t we all,” replied Ruti, with a cracked voice. Musa shook his head.

“You didn’t?” Ruti asked in disbelief. “Not one member in your family, a friend?”

“Most of my family left in the first attempts of war in 1959. I stayed behind,” The men overhearing them were astounded. They couldn’t even raise another question. The pain they had shared moving the corpses convinced them that he, too, had lost someone. They believed he had taken someone if he hadn’t lost someone.

“When the president’s plane was shot, I was a doctor in Butare. We heard the news and ran towards Burundi for a week. From there, a group of us heard that the Patriotic Front was gathering in Uganda, and we moved there for help,” Musa said slowly.

He paused to focus on the road. “They trained us for weeks, and we started to fight back. I haven’t heard from my family since then.” Before anyone could say a word, Musa parked the car in front of the market gate. There were soldiers in military uniforms. They closed in on the car, checked the back of the truck and waved them to continue forward.

“That always creeps me out,” announced Ruti in a low tone.

“You didn’t serve,” remarked Musa. Ruti jumped out of the car, and they unloaded the bodies. They sprayed the bodies to minimise the smell, took portraits of the remains and cleaned themselves.

“Will you come with me to Gacaca?” Ruti asked again moments later, and Musa finally agreed. They drove back to town, though there wasn’t much within it for it to be called one—a couple of boutiques here and there and people carrying sacks returning to their homes.

THERE WAS LITTLE hope that nothing so monstrous would ever happen again, so people left their boxes packed, the images of swinging machetes etched in their minds. Ruti sat beside his wife at the outdoor court while Musa sat behind. In the far front stood three men in rose shorts and shirts. Opposite was a judge announcing the sentence the first man on the right was receiving. The lawyers signed some papers, and a few police officers cuffed the man and put him in a police car while he yelled in regret and then anger. He apologised, then he warned them he would do it again.

The judge called on the next defendant to step forward. The bald guy leaned on the tall table before him, and suddenly, people started to shout. His crimes must have been grievous. Musa noticed Ruti crying. This was the man who’d taken his sisters. Ruti held his wife’s hand tightly as though he would detach it from the rest of the body. One by one, witnesses came forward, and the victims testified. When the judge’s gavel echoed through the streets, the man on the stand was sentenced to life imprisonment. Ruti jumped in the air upon the announcement. In sheer excitement, he turned around to hug Musa, who held a plain face, neither stoked nor concerned.

“We should celebrate; cook a nice dinner,” said Ruti’s wife. Ruti agreed and invited Musa on the spot.

“Thank you, but I can’t,” replied Musa.

“Oh c’mon, what else are you going to do?” muttered Ruti. But Musa had things to do: a brief routine that involved news, Congolese music, washed-out food and insomnia. It wasn’t pleasant, but he was content. “Next time, maybe,” Musa said.

Ruti grabbed his arm and pulled him aside so that he was not too far from the chairs of the court. “Please, do it for me, for this win,” insisted Ruti. “Don’t be alone tonight.” Musa hesitated but eventually agreed. He offered to drive Ruti and his wife back to their place. They lived just below the parliament offices where the showdown had taken place, where it was silently and proudly announced that Inkotanyi had won the war.

On their way, Ruti introduced his wife to Musa. Barbara was her name. She was sitting in the back, but Ruti glided his hands through the chair and held her. She asked Musa if he was married, but Ruti answered the question. Barbara groaned in disappointment. She hoped there was someone she could talk to while the men reared themselves into their political discussions.

“Make yourself comfortable. Give me time to cook you something delicious,” announced Barbara upon reaching their home.

“Ngwino,” said Ruti and guided Musa into the living room. Come along. A maid served them some Urwagwa (banana champagne) stored for months. He looked at the oil paintings on the wall and felt remiss. His house was nothing like Ruti’s. No decorations and no character.

“That’s the white man’s art,” mentioned Ruti when he caught Musa staring at the paintings. “Found it in a pile of stuff they left behind running. It is rumoured to be about being content with yourself. Rubbish.” The painting was of a woman dancing in her colourful living room. A vase of flowers sat on a table behind her, and a beautiful town was outside the window.

“It doesn’t feel rubbish to me,” Musa said. It accurately portrayed his life.

“I guess I’ll give it to you then,” Ruti exclaimed. They toasted to the Urwagwa in the name of justice and peace for the souls lost in the genocide and love that they desperately desired to return to. At the dinner, Barbara cornered Musa with suspicious questions. “So, where’s your family now,” she began.

“Burundi,” he quickly answered, trying to focus on the Irish potatoes, Akabenzi and boiled straws spread in front of him. Safe to say, he had relinquished his desire to eat after seeing good food for once after all these months.

“Are they coming back?” followed up Barbara almost immediately.

“I have no news on that front,” Musa replied.

“Why aren’t you in the military anymore?” asked Barbara. Musa instantly turned to Ruti, rolling his eyes to ask how she knew. Ruti tried to steer the conversation away from where it headed: the past. The long, traumatising nights that everyone wanted, destructively, to forget. He failed.

“Was it too much?” besieged Barbara.

“I guess it was,” said Musa. “I never really chose to be a soldier. It just happened. And along the way, I kept losing myself. So I promised I’d quit if we ever won, and it’s over.” Barbara stared at him with empathy, then gave him a look that distorted the idea that she’d understood what he meant.

“Did you kill anyone?” she asked.

“I saw a lot of deaths, a lot more than anyone should,” Musa said. Barbara tried to re-ask her question, but Ruti held her hand back this time. He tilted his head as she faced him, and the questioning stopped. It was getting late—the kind of time where no one dared step outside their house anymore, but Musa wasn’t a man of fear. Not anymore. Not after seeing kids lying in the streets over their parents. Not after he had to wrap their bodies in plastic bags and lift them for days on end.

“See you tomorrow, Ruti,” said Musa, exiting the gate and hopping in his truck. Ruti watched him cruise into the night and fade. That night, Musa didn’t turn on his TV. He lay on his bed and slept like a baby. He didn’t show up for the next few days for the cleaning. He bought a pile of wood from the carpenter down the street and made himself a good lunch table, a solid bedsitter and a stool for exactly one visitor. He stacked sacks of rice, sweet potatoes, beef in the fridge, and charcoal behind the elegant stove he’d found unharmed inside a beautiful apartment in Kiyovu. He sat by his window overlooking an empty hill separated by a valley of unattended Sorghum and sugarcane crops overlapping each other and dying out in the sun, a cup of tea in his hands. The view was beautiful. It had always been, but he couldn’t remember the last time he’d stayed still for a moment and took in something. It had been so long since Rwandans had been themselves. They weren’t there yet. Some argued they never were and remained easily manipulated into hating one another. Maybe that’s what being a Rwandan meant—deprived of their own culture and needing to find it and themselves. He contemplated the struggle to preserve himself despite colonialism and how the names they carried were only partly theirs. They baptised into the rest. Musa Angelo. Ruti Ephrem. They removed people’s uniqueness, replaced them with commonality, and manipulated them into letting guards down. They wondered at the West and the French, who harvested the country’s gold and told the people it was art.

AFTERWARDS, HE LEFT to wipe his cup above the sink like he had wiped landmines from a body down a creek in Gatsata and rinsed his plate and fork through the water as he had done with his hands when they picked up a mother and her son from Nyabarongo. Still, his hands didn’t shake when he returned for the cleaning because Ruti was filling it with his plans of having a kid with his wife. The baby was on his way—six months till delivery. Musa didn’t find this a good idea.

“Why would you do that to the kid?” asked Musa.

“Do what?” wondered Ruti.

“Bring its soul into this life?”

“Well, how are you content with living by yourself?” Both men labelled a body and pushed it on a cart towards the truck.

“I can’t bear putting someone else in this world to go through what I have gone through,” Musa said.

“What tells you they will suffer as you have?” asked Ruti. “What if instead of destroying, they rebuild?”

“That is a tough thing to believe,”

“I’m sorry, but life isn’t always like this. Sometimes it’s beautiful, Musa. We were just unlucky.” As soon as Ruti spoke those words, he found he was stuck in a hole filled with bodies that had taken a hit to the skull. They were conversant with the bodies of machete victims. His leg wouldn’t budge as one of the heavy cadavers leaned on him.

“Err, tell that to these bodies,” grunted Musa. “It’s a stupid idea. The kid is just going to suffer.”

“He’s not. We will shield him from the pain, raise him to be better, and help make this country good,” Ruti snapped. He had been trying to force his right leg out of the hole but to no avail. “Could you help me?”

Musa, now noticing what was going on, gently and quickly put down the body he was carrying and went in to rescue. He pulled Ruti’s arm to give him a boost, but that didn’t work. He grabbed his leg, lying down to gather enough strength. They pulled once more and, once successful, Musa rolled on the ground, laughing before getting up. But the hole had more surprises in store. A grenade cupped between the bodies had not gone off when the perpetrators had thrown them into some of the holes. It, too, had been stuck until that moment when, in the blink of an eye, it exploded through the hole, so near and so loud. It shredded the remaining bodies stacked on top of each other in the hole. More so, it took Ruti’s legs with it.

Musa, who by that time was walking away unscathed, turned to the screams and relentless agony of Ruti and, like the soldier he had become, calmly put his knee down, lifted Ruti on his shoulder, slid him through the backseat and sped through the sand and dirt of the roads heading to the hospital.

“Aaaah, I can’t feel my legs!” whimpered Ruti. “I can’t feel my legs!”

Musa accelerated even more without any words of reassurance or comfort. He’d seen death and didn’t want it to catch up with the car. The hospital could barely provide medicine, let alone handle an emergency, so they brought a prominent surgeon in the city. Musa, as a doctor himself, even assisted once. They stitched Ruti up for hours, and Barbara paced back and forth outside the operating room non-stop. She received news from Musa merely the following day.

“He won’t be able to walk again,” Musa said to Babara. She fell on her knees and cried before Musa, who hugged her and apologised in an attempt to comfort her. He had let his guard down.

“It’s not your fault.”

THE NEXT TIME Musa saw Ruti, he was at his house. The cleaning had ended. The country was finally ready to start over. The military was tasked with finding perpetrators scattered around the country, a mission that lasted around three years. Ruti was sitting in a wheelchair, riding through the house with a baby girl between his arms. He grinned the entire time. Musa saw something he’d forgotten existed for the first time in so long: Beauty. It was not like the kind he lurked at from the window in his house. It was better; it was in people. He understood that darkness could hide the light, but light would always prevail. When it did, memories of little children shot through walls of a church and of mothers thrown from the sixth floor of the Hotel Des Milles Collines and into a pool of blood transitioned smoothly into the tingly satisfying visual of a baby smiling at the slightest lip movement.

“You know, Musa, even after everything I’ve been through, I believe there is nothing worse than being alone,” said Ruti. “I don’t think I would have survived the pain if I had no shoulder to lean on.” Musa leaned back in his chair. He held in one hand a cigarette and, in the other, a stench from the mud he’d stepped in and almost fallen in whilst coming inside the house.

“And I think you know that already,” added Ruti.

“How can you be so cheerful?” wondered Musa, “You just lost your legs?”

Barbara walked in on the conversation with a plate of doughnuts and biscuits. “Rare to find these anywhere these days, enjoy,” she said on her way out.

“It might be a cruel world, but when I’m sitting here with her, the world isn’t such a bad place,” mumbled Ruti, picking one of the biscuits. Musa grinned, and he smoked again.

“We birth kids hoping they make a better Rwanda, so our history isn’t just horror stories,” added Ruti in a calmer voice. “Or at least that’s why I have done it. No killer will eradicate my family, and maybe the kids might even have the courage to forgive.”

“Let’s hope that it will be the case for everyone else,” Musa said, lighting another cigarette.

“I mean, you’ve seen so much death. Don’t you want the future generation to see at least some life?” Ruti asked with enthusiasm. He giggled, gently swinging his baby, his light. Musa watched him. Ruti was right. Someone had to see a better country. He was tired of blood and tears. Someone had to see the other side of it. He stubbed out his cigarette on the cup on the table’s edge, stood up, and hugged the two tightly. One in a wheelchair, the other broken. The hug went on longer than expected. When Musa rose, he found he’d cried a little.

“I’m sorry for everything,” whispered Musa.

“Don’t be alone,” ordered Ruti, wiping his tears off his jaws. The sun descended behind the mountain ahead, its rays showering on the house. Musa descended the stairs back to his car. He hugged Barbara goodbye and waved again to Ruti, who was stuck in the doorway.

“Mind that big heart, Ruti,” Musa shouted from his car, “It will beat longer,” Ruti smiled and waved back. Before he turned the engine on, Musa heard evening birds sing. The sound rang in the twilight like the Congolese songs on TV. He paused, and he listened. For a split second, he stared reflectively into the distance as if remembering things he had not thought of for a long time.

Ruti watched Musa’s car avoid the potholes that would become grounds for apartment complexes. He saw him slip into the forests that would turn into shopping malls and plod through the loamy streets that would transform into highways. He watched him disappear into the silence of what is now the noise of Kigali Heights nightclubs. Musa never returned.

Patrick Shyaka is a Rwandan author of the short story collection “I Will Get Drunk,” a visual storyteller and copy editor of SENS Magazine. His works have been featured in several reputable literary journals, including Brittle Paper, Lolwe, Isele Magazine, African Writer Magazine, The Kalahari Review, Writers Space Africa, etc.