Blood and Iron

Oma Ifekwem

Background

On July 6, 1967, the Nigeria-Biafran Civil War began when the Nigerian government launched a military offensive against the secessionist state of Biafra, leading to the loss of many lives.

THE IGBOS ARE known for their fierce pride. They accept their pride as part of their heritage, wearing it like the traditional leonine-designed cloth associated with elders of worth. It is this pride that held up 17-year-old Achunike’s quaking knees when they threatened to give way as he snuck off with the rising sun to join the Biafran army congregating in Enugu, the old coal city.

Achunike revelled in reading everything he came across. Since the missionaries taught him and a select few to read, he had found an affinity for it, and seeing both his parent’s delight in this new ability, he had honed it to the point of expertise. Every Affor market day, his mother would take him with her on the pretext of helping her with her heavy basket of yams, and once settled, she would make him read to the traders, who watched in quiet wonder. Sometimes, he muddled up a sentence or two, but he carried on with poise, and no one was the wiser for it.

When the rumours of war began to spread, Achunike read every paper he could find on the pogroms and preceding coups and listened to his father’s radio as often as possible. He kept abreast with the news and kept his kindred informed. While other young men rallied themselves to a frenzy and could not wait to join the Biafran army, Achunike was careful to keep his thoughts to himself. He had read enough to know that when elephants fought, the grass suffered. The powerful fought with words and gallant stances on guarded podiums, while the poor were sent to the battlefield to die. He was no fool. He would not be drafted into the army, and he was certain his mother would back him up on his decision since he was her first son, her Di-Okpala. If the time came, as was rumoured and drafting became forced, he knew exactly where to hide and never be found. Achunike was prepared.

With that mindset, at peace with his decision, Achunike went to Idemmili River to fetch water at noon. He preferred high noon because the river was usually deserted. The morning rush was over, and the evening one was yet to begin. He whistled as he walked up the winding path through the lush greenery surrounding the sacred river. It was a beautiful day, and he intended to enjoy a quick swim. Like all Idemmili children, he was comfortable in the water, and any opportunity for a swim was welcome.

Achunike’s pleasant whistling abruptly stopped as he saw a frail figure hunched near a small rock.

“Who is there?” Achunike called with concern.

“It is I,” came the soft response. Achunike hurried over to the boy, his brows furrowed in worry and annoyance. ‘I’ was not a name! He thought, but he was too polite to point it out.

“Are you all right?” He asked instead, and as the words left his lips, he wished to take them back, but it was too late. He could see the boy was crippled. Achunike wondered how he had gotten up there, who had brought him, and why the person had left him alone.

“I know the tune you were whistling, coming up to the river,” the boy told Achunike, brooding.

“Yes, it is the warriors’ chant,” replied Achunike cheerily, trying to cheer up the sad boy. He had an ethereal beauty, which made his disability more pitiful to Achunike, who worried on the boy’s behalf that in adulthood, he would have difficulty finding a wife. The women tended to go for the huge, muscular wrestling champions. Even he, Achunike, knew his prospects weren’t that good as he was rather lithe, but he made up in wit what he lacked in physique.

“Are you a warrior?” the boy asked, eyes slightly widened in amazement.

There was no need to disappoint the poor boy, so Achunike puffed out his not-overly-impressive chest and responded with as much pretension as he could muster. “Yes, I am!” As an afterthought, he added, “And I am descended from a long line of warriors.”

At least that part was true, overshadowing the lie, on the off chance the boy decided to ask around and found out he was fast becoming the village orator and not a warrior.

“Then you will fight for me!” The boy declared.

“Point out who bullied you, and I will deal mercilessly with them,” Achunike grinned back, acting. A stern scolding would do the trick, but there was no need for the boy to know that. The boy clapped his hands in glee, doing a little slithering dance.

“Say you will fight for me,” He insisted.

“I will fight for you,” Achunike responded. He knew he had erred as soon as the words left his mouth. He should not have given those words so freely and carelessly, a deep instinct that normally laid dormant whispered to him urgently. The words had become binding.

“But who do you want me to fight?” Achunike asked urgently, unease evident in his voice.

Seeming to ponder, the boy, looking to the riverscape, said, “Dark clouds gather, and a storm brews. The rivers will run red with blood and the desolate fields with pain. Suffering dances into the horizon, and famine cackles alongside her, mad with glee. The reaper follows behind, anticipating a gluttonous feast. My children’s existence lies on the scale, and it tips not in their favour.” The boy took a heavy breath and turned his gaze on Achunike. “But one will bend the scale with his will of iron and stand between my children and the Overlord, who must be paid in blood.”

Achunike felt the weight of the cripple’s words permeate every iota of his being, and it was almost too heavy to bear. Goosebumps broke out all over his body as he took a closer look at the sitting child; this was no child but the python deity in one of his forms! Achunike berated himself as he should have known. He was usually very observant, but for some reason, his senses had failed him today. The signs were clear as day, for no matter the form the deity took, it was always crippled. How had he not recognised Eke Idemmili immediately? As he fell to his knees in reverence, Achunike woke with a start. He jumped up, absently wiping the drool from his mouth. He had fallen asleep on the river bank, which explained the strange dream, but as he rationalised, his mind began to question when and how. Achunike shut down the terrifying possibility that he had just encountered the python deity and ran down the river path with his empty basin forgotten on the river bank.

Achunike tossed and turned all night as sleep eluded him. He pondered on the dream he had at the Idemmili river bank. Was it really a dream, as he had no recollection of settling down or deciding to nap? One moment, he had been walking up the pathway to the river bank, whistling happily, and the next, he was waking up on the riverbank, very close to the water. Did he faint? Was he ill with malaria and having hallucinations? It was mosquito season, after all.

He kept vigil through the raging battle between his senses and superstitious sensibilities. He was not overly pious, but he kept the tenets of the land, and although he had heard stories of the Python god visiting humans from time to time, he had never anticipated he would be one of the few. Then there was the issue of a promise made to a deity, even though spoken carelessly; it was a sacred oath binding on the speaker and his lineage. The gods forbid he be the reason for the sudden end of his lineage or for his blood to be cursed with generational bad luck.

Before the first crow of the cock ushered in daybreak, Achunike rose with his mind made up. He did not know what was expected of him or how he was supposed to stop death when he could barely stop an angry ram trying to assert dominance. He, who had always shunned physical violence and focused on the strength of the mind, had been chosen, no, handpicked by the serpentine river deity to save his people, and he saw no other way to do that than to join the army.

ACHUNIKE COULD BARELY keep the wonder from his gaze as he held onto a pile of wood in the lorry bed to keep from tumbling out from his precarious perch. The first sighting of the representation of the gods at the entrance of the city, which stood on rocks, was Amadioha, commander of thunder and wielder of iron. Achunike felt guilty about his fascination. The missionaries had hammered into them the sacrilege of acknowledging the deities. Even the ancestors had become taboo, and to venerate them was a sin deserving of steep penance.

Casting aside these turbulent thoughts, Achunike smiled. It was fitting that the people’s uprising should start in the ancestral rocky plains of Enugu, where the imposing iron sculptures of the old gods stood tall and proud. Proud gods of a proud people. This was the crux of the matter. People who had defied taming were rising and grasping freedom with every bit of their spirit. They were outnumbered, out-armed, and out-politicized, but they had that little spark that could not be taken from them and was as stubborn as the Achara weed, their pride.

Enugu was a city like no other. To Achunike’s untraveled eyes, it was the peak of civilization. There was not one mud hut in sight; all around were beautiful bungalows built with zinc for the roofing. He couldn’t believe the show of opulence in the city; most spoke English fluently, and their women tethered around in high-heeled shoes. He had only read about them in books, as the women of his village tended to favour stout and sensible shoes. It was truly the city where the gods disguised to mingle with men. Everything in Enugu looked sophisticated to Achunike. He kept filing details mentally to regale his mother with stories when he got home, that is, if he ever spoke to her again.

Unlike the village mud roads, the roads in Enugu were built with coal tar, and the houses had beautifully wrought iron fences and big dogs to guard the wealthy. Today, the dogs were barking in unison, sensing the change in the atmosphere. Enugu had become a hub and probably saw more people than it had, even during the popular New Yam Festival days. As the young men willing to fight trooped into Enugu, the businessmen and influential traders who called it home drove out in their Volkswagen beetle cars and Peugeot 504s towards the city gate as they whisked their families to the safety of the villages.

IT WAS A hot Thursday in July, and not just from the heat but from the tension in the air. The people listened on the radio as the political drama of the day unfolded. General Ojukwu called his people to rise, take a stand, and fight for the right to be! He was a man with a way with words. His words fueled the fires in the hearts of the Igbos, and they knew that the time had come to fight for their emancipation.

The literate in English became the interpreters to their kinsmen and village gatherings. As one, they all looked up to the charismatic son of the land, who had gone to the white man’s land, learned his ways, and shunned them in favour of his origin, Ojukwu, the warrior son of Igbo land!

The call to arms came over the radio as he gave his speech calling for secession. They were to be called The Republic of Biafra, the land of the rising sun. It was a name that represented hope for a brighter tomorrow, and there was an unforgettable uproar.

Achunike initially had no intention of joining the fight. Although he believed in the liberation of the Igbos, he worried that he needed to be close to keep his family safe. He was the first son and the one who could read and interpret English with ease and timely keep up with happenings and the proper ways to keep his family secure.

It was a fortnight after the speech that Achunike had his encounter on the river bank, and a new conviction took hold—the only way to keep them truly safe was to be at the battlefront. He would not only have first-hand knowledge that way and be equipped to make sure the enemy soldiers never came near his home. He was sure other young men from his village would stand with him. With logic cast aside momentarily and a fire in his heart, the seventeen-year-old boy stole off with the first light of the day to begin his hike from Obosi to Enugu. He was on his way to stand shoulder to shoulder with his brothers at heart to fight for his people. He was walking into certain death, but when a deity comes to you for your help, when it points out that the future of your people depends on your action or inaction, you don’t say no. You get up and move in the direction calling to you the loudest.

He worried, however, with all the reasons why it was a bad decision and to have snuck off without his father’s blessings! Such was enough reason for a father to curse a son. If he turned back, he would mostly receive a well-deserved caning and, in time, would be forgiven, but he queried himself: How can any of us ever be safe if I turn back?

Achunike’s feet kept their onward march. He trudged on till he saw and flagged down the lorry headed for Enugu.

This was how Achunike, the son of Odinaka from the village of Obosi, found his way to the Biafran war to fight for his people and their right to be.

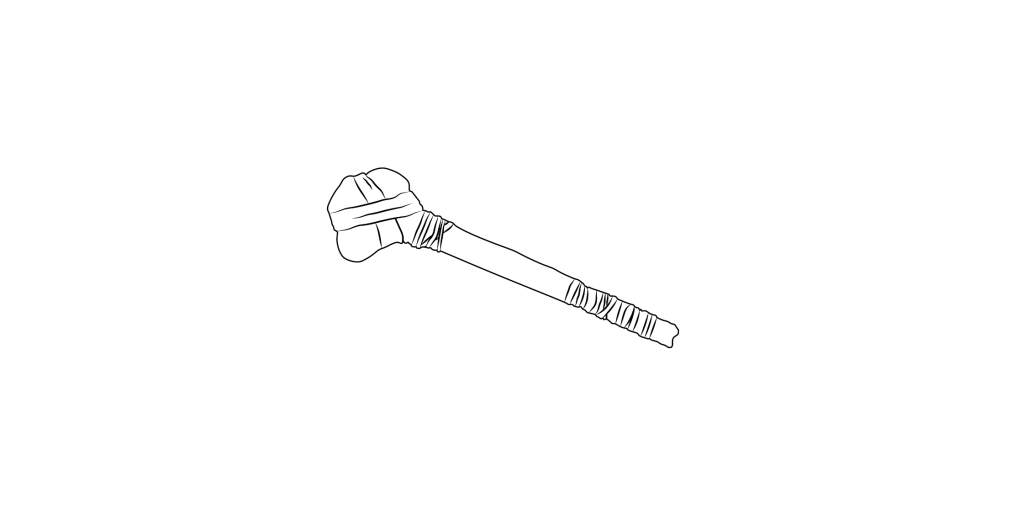

FROM THE START, Biafra was the underdog. On the day Achunike was drafted into the Biafran army, he was commissioned with a club, the lucky ones got machetes, and the soldiers of repute who had defected from the Nigerian army got the few guns available. Achunike stared at the club with renewed panic. Why had he let the hallucinations of a fevered mind lead him on this treacherous path? He thought as he fought the urge to turn and run. He was still contemplating a good escape route when he heard a barely controlled war cry as one of his fellow recruits threw his machete up in the air and caught it with gallantry. The soldiers all around cheered with fire in their eyes. These men were not afraid! They already knew their opposition comprised trained soldiers armed with assault rifles and armoured tanks, but everyone in the barracks didn’t seem to care. They were fighting for the right to be, and that was all that mattered. Achunike didn’t join in the courage-bolstering chants and war cries, but he didn’t leave the parade ground either; he stood there quietly with his club clutched to his chest and a new gleam in his eyes. Without knowing it, bravery, conviction, and passion were slipping into him like contagion.

At the point of the draft, Achunike was sent into intensive training with other conscripted soldiers. They learned endurance, shooting, hand-to-hand combat, and guerilla warfare. He was becoming a valuable member of the 11th division under Major Joseph Achuzie. Achunike wasn’t the best in shooting or some of the other military tact, but his natural inclination as a son of the Idemmili River and its deep forests was evident. He was as sure-footed as a mountain goat, could sit still longer than most of his comrades, and had the stealth of a python in the water. Achuzie saw these traits and knew he held promise. He was not a boy who had come into the war for its novelty or the promise of glory but one who truly believed he was protecting his people. His unspoken rationale was enough for Achuzie to want to mentor him personally. Good soldiers were wanted, but men of valour were needed. Without them, all would be for nothing.

In September, news of the Nigerian army, who had gradually been encroaching and surrounding the eastern lands, had reached Onitsha, the trade hub of the Igbo land, and cornered it like a boar surrounded by hunters’ spears. Conquest was just a matter of time. Achunike felt a moment of intense panic. Onitsha was a three-hour trek from Obosi, his hometown. He had found his way to Enugu to stand as a protective barrier for his people, yet the enemy had snuck past through Ibusa, a neighbouring town, and was edging closer to his home and all he held dear.

The order from General Ojukwu was clear: defend and reclaim Onitsha, and in less than four hours, Major Achuzie’s battalion was stationed with the 18th and 12th divisions. This would become Achunike’s first taste of the actual battle. He had spent three months training and thought himself ready though he could not stop the trembling of his hands, no matter how hard he gripped the rifle he had earned. They took positions, settling into the muddy banks of the river Niger around the bridge, named after the river, which they had blown apart as part of their strategy..

ACHUNIKE DID NOT remember the exact moment or action that signalled the beginning of the battle, but all of a sudden, the air rang with the jarring sounds of gunfire, and for some reason, he forgot to fear, and his focus became razor-sharp. No Nigerian soldier would get past him, he swore. Amid the cacophony of gunshots, cries of the injured, and grunts of the dying, Achunike remained engrossed in keeping back the enemy that a strange sense of calm came over him. He had somehow found tranquillity in the moment. He centred himself, took aim, and fired. There was no endless supply of bullets, so they were taught to make every shot count. Achunike became the hunter, and he was a problematic hunter. With a wall of defence made up of men like him, it was becoming difficult for the Nigerian Army to advance. A special squad from the 12th division had been dispatched to incapacitate the tank approaching Boromi under the Nigerian flag. The fact that there was no tank in sight was welcome news, and the men of the Biafran army held the front with the intensity of a bee hive.

The feel of liquid splashing violently into his eyes jarred Achunike. He turned to see his friend Paul staring sightlessly beyond what could be seen. He and Paul had bonded over folklore told in quiet voices when they should have been grabbing what little sleep was permitted. They had exchanged stories and helped each other imagine the unique beauty of their hometowns. Paul was from Akwa, a town that revered Monkeys as messengers of the gods. He had been given a Christian name by a mother grateful to the Christian nun who had helped her through a difficult birth. Paul and Achunike promised each other that they would visit after the war was won and done. It had become a prayer, words of hope to help cajole tomorrow into being. And on the very first day of battle, here was Paul with half his face blown off into a grotesque mask of death. Achunike tried to rush up and away from Paul’s brain matter all over him, and that would have cost him his life if not for a rough hand that pulled him down and held on till his struggles subsided. Achunike had gone blank with terror and did not recall the face of the comrade who saved his life. All that registered was the vicelike grip that held on and wouldn’t let go till his burst of muted hysteria ended, his vocal cords clamped down as everything in him fought to escape. For Achunike, this was when the materiality of the war hit. This was no child’s play. It was an intimate dance with death, and he could barely keep up with the beat of the dirge drums.

By the end of that day, Achunike was numb from the shock of the horror he was living. He was shoved to the back of the defence line with a grunted command to gather himself. Everything onward failed to register in his mind. He went utterly blank, but for the constant ringing in his ears that wouldn’t go away. The ringing had started the moment he looked into Paul’s sightless eyes.

Oma Ifekwem is a Nigerian author who juggles family life, a successful corporate career, and her passion for writing historical fiction. An avid annals enthusiast, Oma studied Political science focused on past life-changing events in sub-Saharan Africa. From an early age, she learned to really listen to and recount stories from the older generation. Oma cares about humanity and strives to create awareness of social issues that plague African societies.