Dolphins at War

Linda Jummai Mustafa

Background

On July 6, 1967, the Nigerian-Biafran Civil War began when the Nigerian government launched a military offensive against the secessionist state of Biafra, leading to the loss of many lives.

My passion for dolphins started after my father told me how dolphins saved their lives when they were shipwrecked during the Nigerian civil war. Dad told us that their ship, NNS Ogoja, was shot by a missile from the hinterlands of the Eastern waterfront. The bomb, then known as “Ogbunigwe,” which means “a killer in the heavens,” blew their ship in half, and as it sank, they scrambled out of the ship, abandoning it for the lifeboats that were tied to the side of the huge ship.

Frightened and confused, they scampered into the lifeboats and hurriedly paddled their boats away from the sight of Biafran soldiers. Unknowingly to them, they had ventured too deep into the sea, and away from the coordinates that the Nigerian Navy could easily use to rescue them. For days, they stayed at sea, with no food, water, or communication with land, and at night, they held their breaths in fear because they could not see each other. The sea was pitch black, smelly, and extremely quiet, except for the sounds of clashing waves that tossed their boats up and down. Days went by with hope, but the nights were lived in fear; still, they waited for help even though there was no sign of a rescue mission. With the only walkie-talkie he had grabbed while jumping into the lifeboat, my dad tried desperately to communicate their dire situation to the headquarters in Lagos, but it was to no avail.

They were on troubled waters for days, drifting far away from the creeks where they had fired their rockets some days before. The Biafran soldiers had endured several hits from their ships, but they quickly recovered to counterstrike against the Nigerian Navy warships. It was a huge shock to my dad and his crew members when the first bombs struck their ships. In the bombardment, two ships were destroyed, and some men died in the fury of the attack. Alone at sea, several attempts to get the Naval Base to respond to their SOS were carried out, but only crackling static sounds over the walkie-talkie were heard. Due to their inability to contact base, they began to fall into depression. They were cold at night, shivering all through the dark night, and during the day, the hot, humid air was harsh on their bodies.

With no land in sight—and no means of mapping out the drift of their boats—they could not calculate the actual coordinates that could be used to trace and rescue them. In those days, ships used radar equipment to navigate their way through endless waters to their destinations, and my dad was one of the best radar and communication officers recruited into the Nigerian Navy. Although he earnestly sent desperate calls to the Lagos port in order to draw the attention of ground naval officers to their predicament and also initiate a rescue mission for their sake, there was no response, and all his efforts came to nought. He had called Apapa port for the hundredth time; still, no one answered his radio call. Soon, the crackling sounds that the walkie-talkie kept spurting out damped their spirits as they all thought they would die from hunger, thirst and dehydration. They had been at sea for two days now, floating farther into the deep black sea with no hope of rescue.

Before the abandonment of their ship, most of the officers of the Nigerian fleet could not effectively explain why, for the last five months, they had been operating in the creeks of Warri and Calabar, battling the Igbo revolutionaries whose mode of operation was similar to that of the guerrillas of Cuba. Now that they were abandoned at sea, my dad and members of his crew believed that the war was a show of egos rather than a need to keep the country together. Why would top officers from both sides not see eye to eye? Whatever would have caused their differences shouldn’t have escalated into this war, so many people were dying and for no fault of theirs. In that moment of hanging between life and death, my dad thought of the war, his lonely death, and a Nigeria that may never be because of irreconcilable differences between Major General Yakubu Gowon and Major General Ojukwu. He was sad that none of the angry Generals thought of the thousands of men and women who must die for no fault of their own.

As they silently awaited death, the shipwrecked naval officers saw rockets exploding in the sea in daytime. Some were a near miss, and others troubled the sea to such an extent that the waves, foams, and windy air that emanated as a result of the explosion of the bombs almost capsized their boats; at night, when the Biafran side had rested for the day, dangerous man-eating sharks surrounded their boats. They were terrified when they thought that they had escaped death by a whisker, only to die horribly at the jagged teeth of sharks. With this knowledge, my dad and some of the men cried.

However, even with fear in their hearts, Daddy kept calling base until the walkie-talkie gradually began to blink and beep weakly till it stopped working. All his efforts at getting their SOS through to headquarters had yielded nothing, and they were virtually on the edge of losing their sanity as they listened to the weak crackling sounds of my father’s walkie-talkie.

The officers were depressed as more and more sharks continued to encircle them. To the men sitting in ten lifeboats, their escape from their sinking ship seemed to have belittled the carefully crafted design and strategy of God to help them escape the torture they would have suffered at the hands of Biafran soldiers. So, as they thought of the gory end that awaited them, they earnestly prayed for divine intervention, which, unknown to them, was already happening.

Unknown to the stranded men at sea, dolphins had surrounded their boats as the sharks swarmed around them. These dolphins were the reason why the lifeboats had not been attacked by the sharks swimming stealthily around them. The dolphins made a ring around each boat, happily swimming and jumping up into the air from time to time, with a strategy to dissuade the terrifying sharks away from the lifeboats. If they sensed any danger to the lifeboats, the dolphins would make clicking sounds to summon all the dolphins to encircle the loose rings they had made around the boats. The dolphins would whistle loudly too, but my dad was unsure which call was a call to fight or a call to play. To their utter amazement, they later discovered that the dolphins had, all along, put up a formidable block against the sharks in order to protect them.

It was a thing they had never imagined. In the middle of the sea, just as they had given up hope of ever returning home, dolphins would not let sharks kill them. For three days, dolphins bravely fought off ferocious sharks away from their boats until rescue finally came. On the rescue ship, my dad and his friends stood on the deck waving at the happy dolphins. They were mesmerised by the simple fish that saved them all, and they were not known to them. It was really a strange thing for a school of fish to come from nowhere to save men who were sent to kill other men. The irony could not be mistaken, and from that moment on, my dad looked at animals (especially dolphins) differently.

The dolphins were still not satisfied that the men they had surrounded for three days followed the rescue ship. They swarm around the ship, making clicking sounds as the ship moved towards Lagos – Apapa port. After about thirty minutes of following the ship, the pod of dolphins began to slowly swim away from the rescue ship until they could no longer be seen.

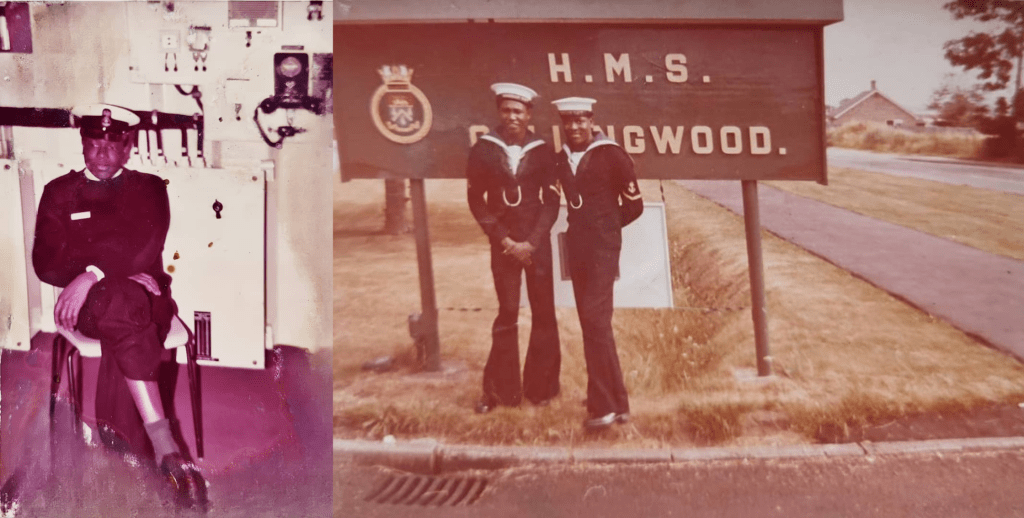

Having successfully disembarked from their rescue ship, my father promised himself that he would learn everything about dolphins and also tell his children about this special fish that sacrificed itself to save more than thirty sailors stranded at sea. He told us about all the good qualities of a dolphin, repeating his miraculous story every time he reminisced about the time he was an ordinary seaman in the Nigerian Navy.

As my sister and I grew up, there was virtually no month we didn’t hear stories about the most intelligent fish on earth. Daddy would tell us stories about dolphins, weaving magical moments as he explained the habits and life of a dolphin. One day, he returned home from one of his sea travels with a giant book about the animal world. This book was filled with beautiful pictures of different animals; their habits, habitats, and their significance to the world. From colourful, dangerous snakes slithering through hot desert grounds, to white polar bears deep in the cold Arctic. With this book, my sister and I discovered a new world that was solely animal-centred and mesmerising. Our worldview on environmental studies changed, and we began to love and value all types of animals. In fact, our knowledge of the animal world brought a new tradition to us—we began to see animals as copartners in trying to bring harmony to a world that had been devastated by industrialisation and other selfish human activities that fed only the greed of humankind, while the climate and environment suffered.

With my love for animals, I yearned to keep a dog, but our living quarters were too crowded for a family to keep a dog. We eventually got to keep several dogs that we loved so much after we moved into our fully fenced house, which my dad had built. Daddy had been building a house for years, and when it was finally completed, we moved in. Soon after, we bought a dog named White, after its white coat.

I had several other sisters and brothers, but most of them were not moved by the stories about the civil war, the dolphins and the miraculous rescue; however, a tradition of being responsible for our environment was born, and it stuck with us. Daddy taught us how to properly dispose of trash by taking it only to designated garbage sites. If there were no designated places for refuse, we carefully burned our trash in such a way that the ash was used to plant vegetables and other small plants.

In all the years we grew up, Daddy never told us what he went through during the Nigerian civil war except for that one encounter with dolphins. To him, the war was so devastating that he barely talked about it. When he did talk about the war, he would be deep in thought, telling us that regardless of our beliefs, ideologies, or political affiliations, we should never encourage war or be part of it. Even though he was awarded medals for his bravery in war, he kept them hidden in his cupboard, bringing them out when he remembered the dolphins that had once saved his life.

In my house, I have so many beautiful figurines of dolphins. Dolphins swimming in the sea; dolphins standing with shells of sea fishes and star fishes; dolphins with other sea creatures; and dolphins happily swimming with humans! The colourful display of these figurines always baffled guests whenever they came to my house. Some thought I was in a cult where we worshipped dolphins, but I would smile back at them, happy that my obsession with dolphins could be traced to my dad.

Dad has gone to the world beyond, and I missed him so much. But he had unknowingly sparked a tradition in me, prompting me to love animals, trees, rivers and lands. Because of dad’s stories about animals, I have come to love animals, no matter how dangerous they may be. No wonder, the brownish colours of wilting leaves, the dark green of mature leaves, the gentle light green colours of sprouting leaves and seedlings, intermixing with colourful wildflowers and animals, tell me that a world that experiences war on its landscape is a world that is on the verge of extinction.

Living in a town close to one of Nigeria’s largest game reserves, the beauty of trees densely populating the landscape of the Kainji Lake National Park is breathtaking and a colourful plea for people living in this area to stop the deforestation of forest lands. Yes, I do get freaked out by slithering snakes and man-eating crocodiles, yet I know I have a responsibility to take care of my environment, especially when animals are concerned. Dad’s rescue by dolphins, his dedication to teach us about a co-partnership with animals, the environment and his aversion to war and all the evils from the Civil War have taught me to love the world with no reserve. As I see the dolphins on my TV stand, I am reminded of a duty to love, not hate; to seek the truth and not believe ideologies that are anti-environmental; and to love, love, love everything on earth and beyond.

Linda Jummai Mustafa teaches African American/Caribbean literature at Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida University, Lapai, Niger State. Her debut collection of short stories, titled What If…?, came first runner-up in the ANA prose prize in 2021, and her second book, titled Kande and the Antelope, won the Open Arts Manuscript Publishing Deal for Northern Women Writers (Sponsored by Ford Foundation) in 2024. She is also a poet, and her poems are featured in several local and international anthologies. She is the first female from Borgu Local Government Area of Niger State, Nigeria, to be a published writer.

Cover credit: Victor Ola-Matthew.